A Writing Lesson From Papa Hemingway

Many people aspire to be great writers, or just writers, period, but have trouble getting started. While nearly all successful writers say the way to be a writer is to write and leave it at that, many believe there is some secret to it – like getting up at 6 a.m. and writing standing up, or inducing an hypnotic trance.

When I listened to Terry Gross interview my former father-in-law, Russell Banks, on her wonderful radio program ‘Fresh Air’, I always got the impression that she was trying to discover the secret of great writing. And I got the impression that Russell, God bless him, was cultivating this idea.

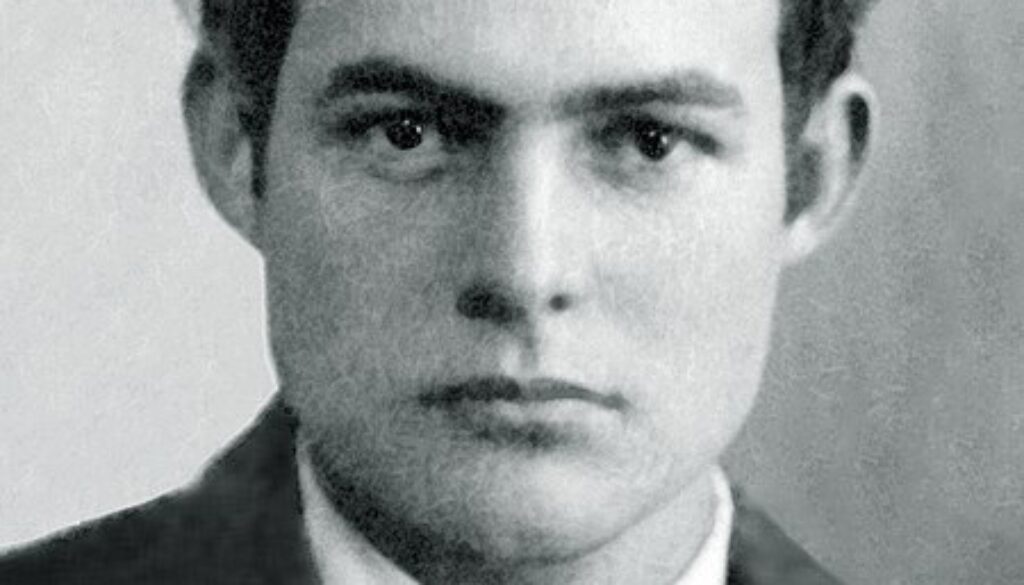

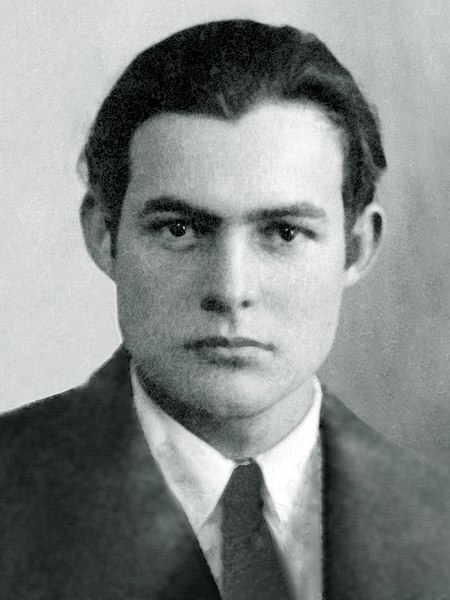

The best practical advice I’ve ever seen on how to write great fiction comes from a book by Ernest Hemingway which he called The Paris Sketches and which was posthumously published as A Moveable Feast, a title chosen by his last wife Mary and publisher Harry Brague.

The book was written in the late 1950s and describes Hemingway’s life in Paris with his first wife Hadley and their son Mr. Bumby in the 1920s when goatherds drove their flocks down the street and milked them for buyers on the spot.

Ironically, it was written at a time when the author was wracked with pain and depression from two debilitating plane crashes and a brush fire in 1954 and was suffering from writer’s block.

Looking back over 30 years, Hemingway recalls climbing to the studio he rented to work in, with his pockets full of chestnuts and mandarin oranges.

“I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day. But sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made.

“I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’

“So finally I would write one true sentence and go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that you knew or had seen or had heard someone say.

“If I started writing elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.

“Up in that room I decided that I would write one story about each thing that I knew about. I tried to do this all the time I was writing, and it was good and severe discipline.

“It was in that room too that I learned not to think about anything that I was writing from the time I stopped writing until I started again the next day. That way my subconscious would be working on it and at the same time I would be listening to other people and noticing everything, I hoped; learning, I hoped; and I would read so that I would not think about my work and make myself impotent to do it.

“Going down the stairs when you had worked well, and that needed luck as well as discipline, was a wonderful feeling and I was free then to walk anywhere in Paris.”

So there you have the secret of great writing: squeezing mandarin orange peels into the edge of the flame.