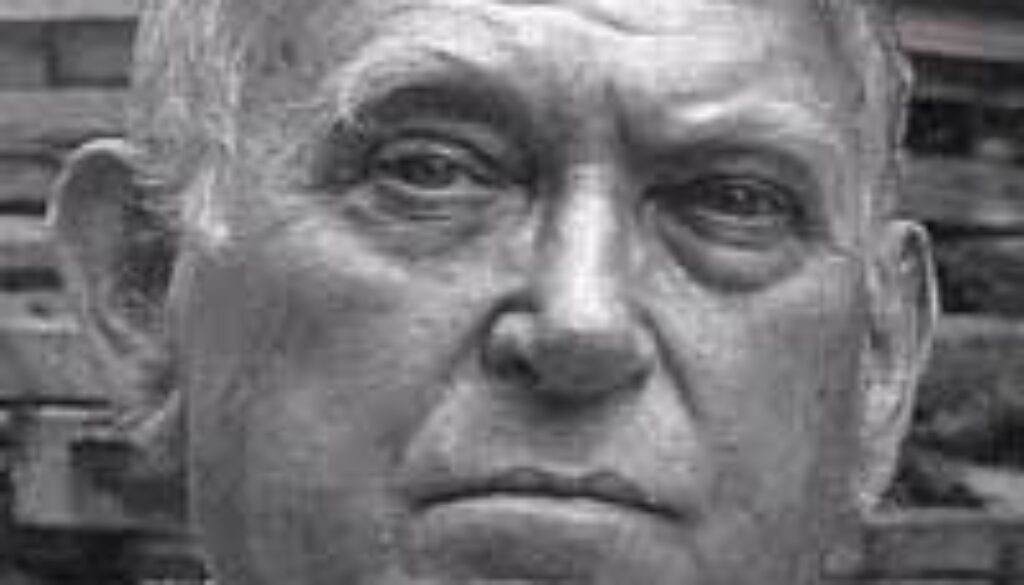

H.L. Mencken and the Wowsers

I picked up the May 1986 edition of American Book Collector (Bernard McTigue, editor) because it had a cover article entitled “H. L. Mencken and the Wowsers” by Jason Duberman.

I bought it to find out more about Mencken, who was a very funny guy in his way, and to learn exactly what is a wowser, but I found the whole story fascinating.

Turns out Mencken actually went to Boston to get arrested on obscenity charges after the April, 1926 edition of his magazine, The American Mercury, was deemed obscene by the Rev. J. Frank Chase, secretary of the New England Watch and Ward Society.

Chase was a Pecksniff, according to Mencken, which is a particularly virulent subgroup of wowser. Wowser was a term used to apply to temperance advocates in Australia and was broadened to denote a person who saps all the fun out of any given situation. A Pecksniff, based on a Dickens character in Martin Chuzzlewit, is one who hypocritically and unctuously affects benevolence or high moral principles.

So all Pecksniffs are wowsers, but not all wowsers are Pecksniffs. After all, it’s perfectly possible to sap the fun out of a situation without affecting high moral principles.

The way things worked in those days, Chase could just declare any book or magazine to be obscene and send a letter to all the booksellers and newstands that they had 48 hours to take it off their shelves. That was it. He didn’t even have to specify which passages were obscene. Any seller who violated his order was dragged into court and fined or even imprisoned.

The Watch and Ward secretary decided to go after Mencken when The American Mercury ran an article about how fundamentalist preaching in the Methodist Church was causing a dangerous rift, with liberal ‘modernist’ members leaving to join the more fashionable Episcopalians, while fundamentalist members were defecting to the Baptists. Chase was a fundamentalist Methodist preacher.

But Chase couldn’t give this as his reason for banning the magazine, so he indicated that the obscene passages were in a story called ‘Hatrack’ by Herbert Asbury — a hell of a story, about which more later.

By the time Chase issued his ban, most of the copies of the April edition of the American Mercury had already been sold, but the publicity made the remaining copies a hot item. When Felix Caragianes, who ran a newstand in Harvard Square in Cambridge, sold a copy to a Watch and Ward agent, he was promptly arrested.

When Mencken heard about this, he got on a train to Boston and had his lawyer contact Chase, offering to have Mencken personally sell him a copy of the magazine. If Chase didn’t show up, Mencken threatened to have a general sale of the magazine and make a mockery of the ban.

Mencken chose as a meeting place the ‘Brimstone Corner’ of the Boston Common, where early New England preachers used to spread brimstone on the sidewalk to set the mood for their fiery sermons. The irony would not be lost on Chase.

Naturally the event drew a big crowd and lots of reporters. Chase eventually appeared and handed Mencken a half dollar in exchange for a copy of the magazine. Mencken, ever the ham, bit the coin as if to see if it was silver.

Chase was accompanied by the head of the vice squad, who promptly placed Mencken under arrest and marched him to police headquarters with the crowd trailing along behind. He was arraigned and ordered to appear in court at 10 a.m. the next morning.

Mencken appeared shortly before ten, but his attorneys were late. This was lucky for him, Duberman explains. By the connivance of Chase and the police, Mencken was scheduled to appear before a judge “who was notorious for his willingness to do as the Watch and Ward demanded.”

“But the court officials had taken a liking to the Sage of Baltimore, and so, during the delay caused by the absence of his attorneys, they decided that the judge’s docket was overcrowded and moved the case to the calendar of Judge James Parmenter.”

“According to Mencken, no one seemed to know very much about Parmenter, except for the fact that he wasn’t an obvious lackey of the Society.”

After testimony by Chase, Mencken, the police, and ‘Hatrack’ author Herbert Asbury, who testified that the story was not fictional, Judge Parmenter took the magazine to read overnight and announced he would render his decision the next morning. To everyone’s surprise, the judge decided that no offense had been committed and dismissed the complaint.

Mencken immediately held a press conference, and couldn’t resist a Parthian shot:

“It seemed a good chance to spread some terror among the enemy, so I hinted at libel suits against papers that had maligned me, and at damage suits against Chase and his associates. I asked one of the reporters… to find out for me what real estate Chase owned. Another reporter volunteered the news that he owned a good house in West Roxbury. I asked where it was and took elaborate notes.

“Finally, I sent for a copy of the Society’s annual report, and expressed great interest in the fact, disclosed therein, that it had an endowment fund of nearly $160,000. All this, I knew, would be carried to Chase by the blabbing reporters, and I was not without hope that it would upset him.”

As I said, ‘Hatrack’ is a hell of a story. A summary from Duberman’s article is in the entry below.