The Real Story of the Amistad

So why was the theology professor walking up and down the New York waterfront counting to ten in the language of the Mendi?

The story of the slave ship Amistad is one that is often simplified to make Americans feel good about their country: a group of Africans enslaved in Spanish Cuba escape their chains, take over the ship, and force their captors to sail to America, the Land of the Free, hooray!

In fact it’s a bit more complicated than that, and if we dip into the complexities of the story, we can learn a lot more about the world at that time and about our country, which was not, at that time, the Land of the Free.

We can also see how individuals, doing the best they could, played a role in the outcome of the story, and in this way changed history.

“The Amistad Story,” published by The New Haven Colony Historical Society is a wonderful volume I picked up at a tag sale which tells the whole story in all its complexity, but also includes some simple facts, which are these:

The captain of the Coast Guard cutter which took possession of the Amistad off the coast of Long Island took the ship to Connecticut instead of New York.

Why? Because slavery was illegal in New York, but still legal in Connecticut, so he could get his salvage claim when the slaves were returned to their Spanish owners in Cuba.

Simple fact number two: the President of the United States (Martin van Buren) and his Secretary of State (John Forsythe) wanted the Africans aboard the Amistad returned to slavery in Cuba.

The Spanish government was demanding the return of the slaves under the terms of Pinckney’s Treaty and the Adams-Onis Treaty which applied to cargoes recovered from pirates.

It’s important to point out that the Amistad was not a transatlantic slave ship, but rather a ship which transported slaves from Havana 300 miles along the coast of Cuba to Guanaja.

The Amistad slaves had been kidnapped from the African nation of Mendi, but according to the Spanish government, they had been enslaved in Cuba since 1820.

Both Spain and Great Britain had banned the transatlantic slave trade, but it was thriving in Cuba, and the American consul in Havana, Nicholas Trist, was “reaping tremendous financial benefits.”

Isn’t that the American way?

The only way to prove that the Africans on board the Amistad were not Cuban slaves was to take their testimony, to show they had been kidnapped in Africa, but nobody in Connecticut could understand them beyond a few basic words.

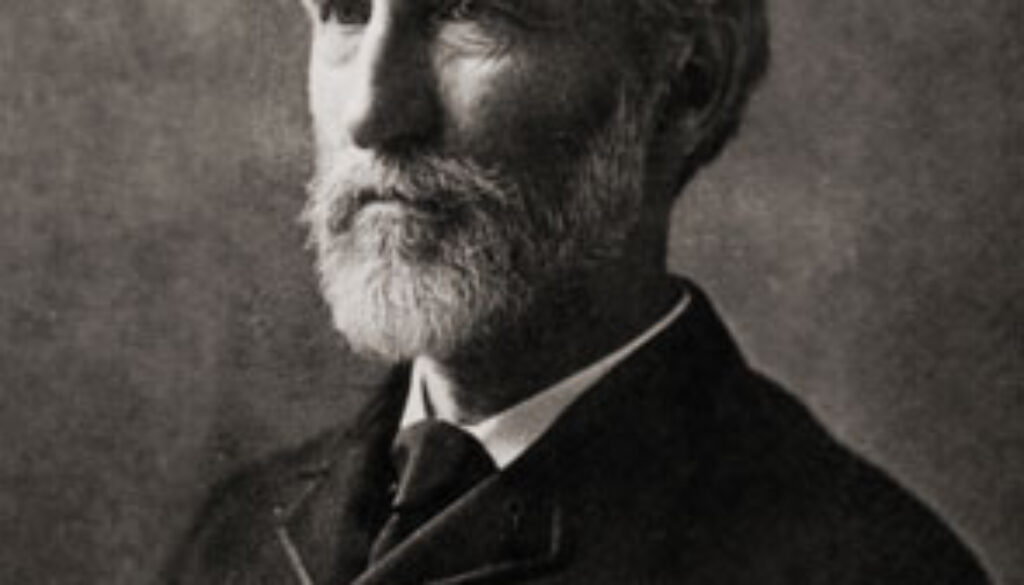

It was then that Josiah Willard Gibbs, a professor of theology and sacred literature at Yale University, showed what he was made of.

He learned to count to ten in the language of the Mendi, and then he walked up and down the waterfront in New York counting in Mendi until he found a British seaman who was familiar with the language and could take testimony from the liberators of the Amistad.

That wasn’t the end of the story, of course. They needed the help of a former president of the United States, John Quincy Adams, to plead their case, but JQA got the job done, and the rest, they say, is history. The slaves on board the Amistad were returned to their homes.

March 15, 2016 @ 11:47 pm

good post